This episode explains the concept of Doughnut Economics and explores how Amsterdam is using it in its post-Covid recovery.

References:

- https://www.cnbc.com/2021/03/25/amsterdam-brussels-bet-on-doughnut-economics-amid-covid-crisis.html

- https://www.amsterdam.nl/en/policy/sustainability/circular-economy/

- https://matchboxstudio.medium.com/designing-the-doughnut-a-story-of-five-cities-8bad04ded5e3

- https://time.com/5930093/amsterdam-doughnut-economics/

Follow the Green Urbanist:

https://twitter.com/GreenUrbanPod

https://www.instagram.com/greenurbanistpod

https://www.linkedin.com/company/green-urbanist-podcast

Thanks for listening!

Join the Green Urbanist Weekly newsletter: Substack

Support the Podcast by Donation

'Economics is broken. It has failed to predict, let alone prevent, financial crises that have shaken the foundations of our societies. Its outdated theories have permitted a world in which extreme poverty persists while the wealth of the super-rich grows year on year. And its blind spots have led to policies that are degrading the living world on a scale that threatens all of our futures.'

That is how the book Doughnut Economics begins. And that is the topic of today's episode. What's wrong with our current approach to economics and what is the solution? The author Kate Raworth puts forward a new model for economics that serves both humanity and the planet. And when you draw this concept, it looks like a doughnut. I'll explain what all this means and how Doughnut Economics is being applied to cities.

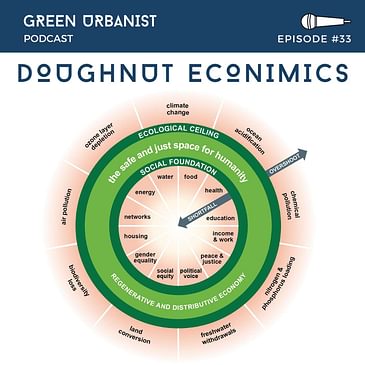

The central goal of a Doughnut Economy, as Raworth writes, is, 'meeting the human rights of every person within the means of our life-giving planet'. This is where the image of a doughnut comes from. Imagine a circle with the centre cut out. The outer edge of the doughnut represents Earth's nine planetary boundaries, which include climate change, biodiversity loss and ocean acidification. The inner circle of the doughnut, the hole in the middle, represents the social foundation of human rights and quality of life. Things like social equity, access to water, food and education. The goal then of Doughnut Economics is to stay in between the inner and outer edges, what the author call the 'safe and just space' of the doughnut.

If we fall short, the economy does not provide a basic quality of life for everyone. If we overshoot, we face planetary tipping points that threaten our very survival. Looked at globally, we are currently both falling short on all social indices somewhere in the world and overshooting a number of the planetary boundaries. Clearly our current economic model is not serving us, which is what Doughnut Economics seeks to correct.

You might be thinking that this all sounds very sensible and admirable. Of course we want to provide quality of life for everyone and of course we want to avoid over reaching the planetary boundaries. But the reason this concept is so revolutionary is that for the most part, traditional economic thinking doesn't concern itself with setting goals like this.

Raworth explains that in the 19th and early 20th centuries, economists sought to reposition their subject away from a kind of philosophy towards a hard science akin to physics or chemistry. Economists of the day set out what they considered to be the natural laws of economics. Laws about how the free market works and how money moves around the marketplace are still taught in introductory courses to Economics students the world over. They form the basis, the world view, of the economic decision making occurring in governments, central banks and corporations to this day. However, the author shows how these models have huge blindspots, ignoring environmental concerns, the role of the household and the importance of communities. In the mid-20th century, the idea of endless and constant economic growth, measured in a country's Gross Domestic Product, or GDP, became the central tenant of economics, conveniently ignoring environmental destruction and the impossibility of infinite growth on a finite planet. The theory goes that economic growth eventually raises all ships. Yes, the wealthy become wealthier, but after a period of inequality, all members of society, or should I say, the economy, raise their standard of living and enjoy a richer lifestyle. The goals of an economy then is to grow, and market forces will take care of poverty and inequality.

This book Doughnut Economics sets out beautifully why this economic theory is has its limits. The richest economies in the world in terms of GDP are becoming increasing unequal, and I don't even have to tell you about ecological destruction and climate change. Raworth acknowledges that for low- and middle-income countries to climb above the doughnut’s social foundation, “significant GDP growth is very much needed.” But that economic growth needs to be viewed as a means to reach social goals within ecological limits and not as an indicator of success in itself, or a goal for rich countries.

That is why Kate Raworth argues for a radical shift in how we conceptualise the economy and it's purpose, and that we need to broaden our understanding of economics to include things like social justice and environmental protection.

She sets out 7 ways to think like a 21st Century economist and achieve the Doughnut Economy. I'll take you quickly through them.

First, change the goal. For over 70 years economics has been fixated on GDP, or national output, as its primary measure of progress. That fixation has been used to justify extreme inequalities of income and wealth coupled with unprecedented destruction of the living world. For the twenty-first century a far bigger goal is needed: meeting the human rights of every person within the means of our life-giving planet.

Second, see the big picture. The economy does not exist in isolation. The market is not self contained. We need to redraw our idea of the economy, embedding it within society and within nature and appreciate the key role of the state, the household and the commons as well as the market.

Third, nurture human nature. Raworth writes: 'At the heart of twentieth-century economics stands the portrait of rational economic man: he has told us that we are self-interested, isolated, calculating, fixed in taste, and dominant over nature – and his portrait has shaped who we have become. But human nature is far richer than this, as early sketches of our new self-portrait reveal: we are social, interdependent, approximating, fluid in values, and dependent upon the living world. What’s more, it is indeed possible to nurture human nature in ways that give us a far greater chance of getting into the Doughnut’s safe and just space.'

Fourth, Get savvy with systems. Systems thinking - understanding how everything interacts with everything else - is an essential skill for solving complex problems like economic inequality and climate change. I did a whole episode on systems thinking back in episode 23, so check that out for more details.

Fifth, design to distribute. Inequality is not an economic necessity, it is a design flaw. Raworth says that '21st Century economists will recognise that there are many ways to design economies to be far more distributive of the value they create'. This means not only redistributing income but also wealth.

Sixth, create to regenerate. We need to move away from the linear industrial processes that cause ecological destruction towards regenerative design that is in tune with the Earth's cyclical processes of life.

And seventh, be agnostic about growth. The author writes, 'Today we have economies that need to grow, whether or not they make us thrive: what we need are economies that make us thrive, whether or not they grow. That radical flip in perspective invites us to become agnostic about growth, and to explore how economies that are currently financially, politically and socially addicted to growth could learn to live with or without it.'

These seven principles are the starting point for reimagining how economics works. The book goes into lots of examples of these principles in action around the world. However, I am especially interested in what this idea means for cities. I love how Doughnut Economics encapsulates and provides a framework for a number of concepts that we talk about here on the podcast, namely circularity - the reuse and recycling of materials to avoid waste - regeneration, which means designing not only to avoid harm but to actually improve the environment, and systems thinking. It puts these concepts into their wider economic context, which is something urban designers and architects often avoid doing.

Let's explore how Doughnut Economics plays out at the city level.

Doughnut Economics in Cities

There are a number of pioneering cities adopting and grappling with the Doughnut Economics concept. A quick look online tells me that Amsterdam, Brussels, Berlin, Sydney, Melbourne, Philadelphia and Portland amongst many others are all working on a local version of a Doughnut and integrating it with city policy.

Kate Raworth's Doughnut looked at the entire planet. There is a challenge in scaling that down to a much smaller scale of a city. In particular, the inner circle of the doughnut, the social foundations, need to be made more locally specific to capture what a good quality of life would mean in a particular city. And so a common starting point for these cities is to create a City Portrait. As the Amsterdam City Doughnut report reads:

"The Doughnut of social and planetary boundaries can be turned into a city-scale tool by asking the very 21st century question, 'How can our city be a home to thriving people in a thriving place, while respecting the wellbeing of all people and health of the whole planet?'.

It is a question that invites every city to start exploring what it would mean to thrive within the Doughnut, given that particular city’s location, context, culture and global interconnections – and the result is the City Portrait."

I think this is a hugely important first step. Often climate change, economics and urbanism can be an incredibly technical topics. And so sometimes we forget that what it's really about is that fundamental question - how can we live a good life? In particular we as urbanists need to help people form and communicate visions for the future so we have something clear to work towards. Avoiding catastrophe is not compelling enough. Reaching technical targets like net zero emissions is not compelling. But Doughnut Economics tells us that the starting point is a shared vision of how our city can help us and the environment thrive and that is pretty compelling. And what it means will be a bit different for each city.

In Amsterdam, the City Portrait was co-created with city staff and local residents, so it reflects the values of a diverse range of Amsterdammers. Some of the social targets that make up the inner circle of the Doughnut, that they came up with are things like 'There is sufficient availability of affordable and decent homes' and 'The city is accessible to everyone via public transport, in a safe and sustainable way' and 'Every child receives a good education in a high quality school environment'.

The portrait also looks at the global level, at how the city is influencing the human rights and quality of life of people in other countries, mainly through its purchasing and procurement.

I think what is really interesting about this is that it is taking topics that have traditionally been in silos, like educations, public transport, housing, food and political voice and pulling them all together under one framework and vision. This is incredibly holistic and forward thinking.

There is also a challenge in adapting the outer circle of the doughnut, the planetary boundaries, to the city scale. The Amsterdam City Portrait does assess how Amsterdam is contributing to global issues like climate change, waste and ocean acidification. And it is definitely exceeding on a couple of these macro indices, which should feed into wider policies.

But it also creates a more locally specific outer doughnut, where it considers the question, What would it mean for Amsterdam to thrive within its natural habitat?

This leads into a regenerative vision of urban design locally. Quoting directly from the Amsterdam City Doughnut report:

"Healthy ecosystems are generous and resilient: they purify the air, cleanse the water, moderate the local climate, cycle nutrients, calm floodwaters, house diverse species, and more – all to keep creating conditions in which life can thrive. What if cities were designed to be as generous and resilient as the ecosystems in which they are located? What if their buildings, greenways, and infrastructure aimed to clean as much air, filter as much water, store as much carbon, and house as much biodiversity as their host habitat does? Doing so would strengthen the health of the whole ecosystem, but also increase the city’s resilience to extremes of heat, rainfall, coastal erosion and drought. This lens of the City Portrait explores seven key attributes of a city’s surrounding ecosystems, including how they: provide water, regulate air quality, regulate temperature, support biodiversity, protect against erosion, sequester carbon, and harvest energy. These insights provide guidance for how the city can likewise live generously and resiliently within the unique characteristics of its habitat."

In Amsterdam, Doughnut Economics is central to its post-covid recovery to ensure that the city does not go back to business as usual. The practical manifestations of this concept so far seems to the city's Circularity strategy, focusing on reusing materials rather than creating waste. So for instance newly constructed buildings now need to include material passports, so individual materials and products can be easily identified and reused if the building is ever taken down. I have an episode coming out in a few weeks that goes into more depth on material passports so keep an eye out for that.

There was another great example of doughnut thinking reported in Time magazine, which wrote:

"When the Netherlands went into lockdown in March, the city realized that thousands of residents didn’t have access to computers that would become increasingly necessary to socialize and take part in society. Rather than buy new devices—which would have been expensive and eventually contribute to the rising problem of e-waste—the city arranged collections of old and broken laptops from residents who could spare them, hired a firm to refurbish them and distributed 3,500 of them to those in need."